Fast-paced trends in cross-border e-commerce are the topic of this briefing. PRC suppliers are setting up their own warehousing, logistics and payments. Together with AI data capabilities, this is speeding up direct delivery to overseas customers. IP issues remain thorny.

Introduction

The world’s no. 2 digital economy, the PRC boasts a thriving cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) sector. Along with local online shopping, it boomed in 2022 as the PRC struggled through the pandemic. The fastest-growing trade mode, it is advancing rapidly as Beijing vies to develop global CBEC rules.

Two-way CBEC trade volume surpassed US$299 billion in 2022, a 8.3 percent growth y-o-y accounting for some 5 percent of total trade. Total CBEC exports stood at US$220 billion by 2022, up by some 8.4 percent y-o-y, while imports increased by 3.8 percent y-o-y to US$79 billion. Total CBEC imports and exports are expected to reach US$363 billion a year by 2025 with annual growth above 10 percent, according to PRC industrial research firm iResearch.

CBEC imports to the PRC respond to an expanding list of authorised products, revised three times since 2016. In 2019, on the back of strong demand, ski and golf equipment as well as dishwashers were added to the roster. Goods switch in and out of demand. Post-pandemic, industry equipment and other non-consumer goods needed to kickstart economic activity are hot items. The flow out of the PRC remains buoyant.

2019-21 total CBEC volume increases, but growth slows

source: GAC

The coastal provinces of Guangdong, Shandong, Fujian, Zhejiang and Henan are the PRC’s major CBEC hubs, taking the top five spots in terms of volume in 2022 or some 70 percent of the total.

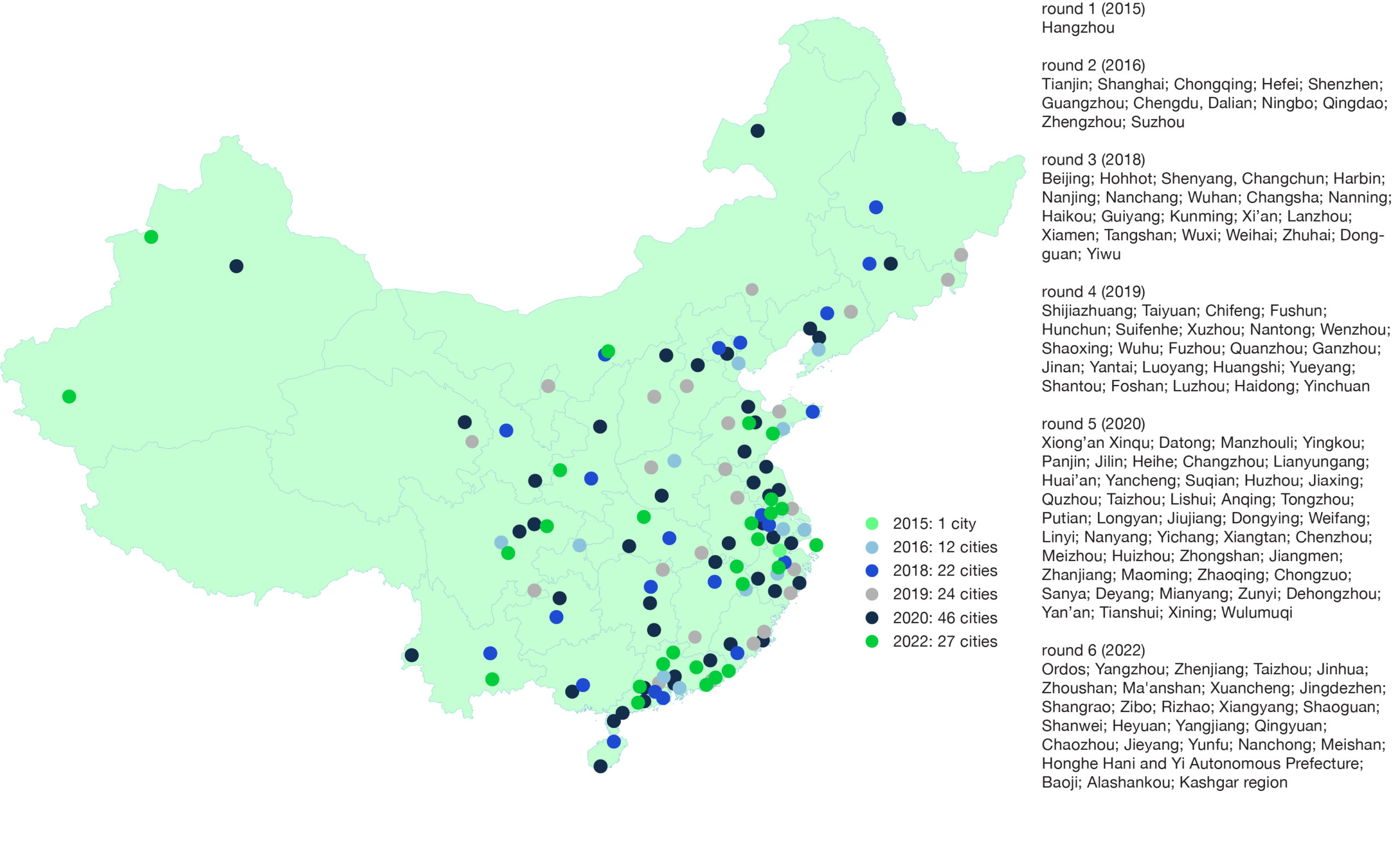

Local policy sweeteners, including subsidies and tax cuts, support cross-border e-commerce firms in expanding logistics networks and localising operations overseas. Incoming e-commerce traders eye up the PRC’s expanded lists of permitted CBEC retail imports and 165 pilot zones scattered across the country.

PRC e-commerce platforms have expanded overseas, above all in emerging markets. Second to Amazon, AliExpress (the overseas service arm of Alibaba) won 24 percent of the global consumer market in 2021, reported Statista. The e-commerce ‘DTC’ (direct-to-customer) model shortens conventional supply chains, reducing transaction costs and helping SMEs reach, and profile, international consumers. Amazon partnered with PayPal and UnionPay on payment services relying on FedEx and UPS for logistics. Alibaba developed its own cross-border logistics and financial solutions while partnering with local digital payment services (see AliExpress case study).

AliExpress no. 2 after Amazon for global market share in 2020

source: iResearch

In Q1 2021, CBEC export and import growth had climbed to 69.3 percent and 15.1 percent y-o-y respectively. But with sluggish overseas demand, an inflationary environment and tightening foreign platform regulations, growth went off the boil in 2022. Customs data records trade via CBEC in Q1 2022 at US$64.85 billion with exports growing by 2.6 percent y-o-y and imports shrinking by 4.2. Publicly listed CBEC firms mostly saw profits plummet in H1 2022. Many suffered the lingering impact of a crackdown by Amazon (May-October 2021) on accounts posting fraudulent reviews. For most of 2022, only 30 percent of Amazon-registered Chinese CBEC sellers made any profit, according to services platform Yuguo. Some R&D savvy exporters were able to steer clear of the anti-fraud campaign and since saw profits jump, reports Yuguo.

Bai Ming 白明

CAITEC (MofCOM research institute) international market department deputy director

While enabling more SMEs to sell overseas and take part in global trade, the CBEC sector is replacing conventional big trade orders with smaller ones. Better customs regulation, inspection and quarantine measures are needed to support CBEC development, set import/export duties, and improve electronic payment systems. A professional CBEC services platform should be set up to help with customs declarations and regulatory clearance. Facing shrinking global demand and rising inflation, export credit insurance needs to support CBEC firms in operating overseas warehouses.

China-Europe Railway’s special CBEC trains will enable Chinese CBEC goods to reach European customers via a faster route, meeting EU demand for Chinese high-tech consumer goods.

supporting policies

A top-level document on advancing ‘new forms of foreign trade’ issued on 9 July 2021, urged expansion of CBEC pilots and encouraged firms to set up overseas warehouses. Ren Hongbin 任鸿斌 MofCOM (Ministry of Commerce) notes CBEC volumes have expanded by a factor of 10 in the past five years. He says further work was needed to

- research and develop IP protection guidelines

- expand retail imports to offer more consumer choice

- streamline return and exchange processing

Responding to the boom in e-commerce, in late October 2021, in an e-commerce 5-year plan Beijing determined to grow CBEC-related deals from C¥1.69 tn in 2020 to C¥2.5 tn in 2025. The plan involved

- developing ‘silk road e-commerce’

- supporting multinational SMEs

- strengthening CBEC firms’ capability to handle trade friction

- engaging in CBEC rule-making

The list of CBEC pilot zones enjoying VAT exemption and reduced consumption tax was expanded in February 2022. Multiplying these, notes Liu Ying 刘英 Renmin University Chongyang Finance Institute, will help curb logistics costs, connect local supply chains and improve the business environment.

expanding CBEC pilot cities, 2015–22

To fast-track CBEC returns services, GAC (General Administration of Customs) in a September 2021 notice, approved setting up CBEC storage warehouses inside special customs monitoring zones. To streamline clearance, a B2B regulation model now operates nationwide.

CBEC firms will face more intense competition as the sector gets more crowded

- Huo Jianguo 霍建国 China WTO Research Institute warns that developing all-round overseas logistics networks will be critical: relying on policy support and extracting profits from manufacturers does not have a long life

- Fu Yifu 付一夫 Xingtu Finance Research Institute urges CBEC platforms to improve big data algorithms that will alert firms to real-time market demand and consumer preference. A cohort of tech-savvy professionals for organising CBEC industrial training programs is urgently needed.

Manufacturing, not downstream logistics, storage, wholesale or retail, is the CBEC sector’s advantage in the PRC, stresses Huo.

But an efficient global storage and logistics system helps position PRC goods in global value chains. Local sales networks and connections ca raise CBEC presence overseas, above all in Southeast Asian Chinese communities. Boosting CBEC in the post-pandemic world will mean more high-end international consumer goods are sold in the PRC and the services trade deficit, a large part of which consists of outbound tourism and shopping, can be shrunk.

Huo Jianguo 霍建国

China WTO Research Institute deputy director

promoting digital silk route

Creating ‘silk road e-commerce’ links with Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) member states has boosted international CBEC collaboration. Since 2016, Beijing has signed e-commerce collaboration MoUs with over 26 countries, including Chile, Brazil, Singapore, Australia, Hungary, Italy, Russia, Pakistan and Senegal. Bilateral sessions have been held regularly, bolstering policy liaison, easing industrial coordination in logistics and digital payment, SME digital transformation, online consumer protection, and more.

China and five central and eastern European countries co-launched a ‘China-Central and Eastern European e-commerce cooperation mechanism’ in June 2021, deepening multilateral dialogue on e-commerce trade promotion and regulatory alignment. A similar mechanism was created between China and five Central Asian countries in 2022.

Localities are urged to engage in ‘silk road e-commerce’ cooperation schemes. Conferences held in Hebei, Shaanxi, Zhejiang, Guangxi and Fujiang in 2021 have helped guide provincial officials. Meanwhile, ‘online classrooms’ went live for authorities and e-commerce traders from partner countries with content covering major sectoral trends, regulatory hotspots, innovative practices, as well as useful toolkits. Live streaming has become a popular way of promoting local goods and exchanging market information.

The China-Europe Railway (CER), a BRI flagship transport artery spanning the Eurasian continent, has emerged as a fast route for quick delivery PRC manufactures, such as daily consumer goods, furniture and clothing. Xi’an, in central China known for being the start of the ancient silk route, has become a major regional CER hub. In 2022, 198 CER trains left the city with C¥3.5 bn of total CBEC goods, growing 40 percent y-o-y.

bringing in goods via CBEC

advanced economies lead PRC CBEC retail import Q1-Q3 2022

source: MofCOM

The scope of retail import pilots for cross-border e-commerce has meanwhile grown to include all FTZs (free trade zones), comprehensive CBEC pilot zones, comprehensive bonded zones, import promotion innovation demo zones and cities with bonded logistics centres.

A three-year pilot for importing drugs via CBEC was launched in Henan province in May 2022, including 13 types of prescribed drugs. The State Council subsequently issued approval in September 2022 for qualified FTZs to pilot CBEC imports of certain drugs and medical equipment.

makeup leads food in PRC CBEC imports Q1-Q3 2022

source: MofCOM

Wang Xin 王馨

Shenzhen Cross-Border E-Commerce Association executive chairman

Four noticeable features are shaping the PRC CBEC industry and driving its growth, including

- consumers moved to buy online from overseas during the pandemic,

boosting further CBEC growth - public and private investment from SOEs and MNCs is growing

- independent digital websites are becoming popular as are visual technologies, such as AR/VR that make such websites more interactive and boost their marketing effect

- increasing value-added inputs are becoming ever more urgent. Rising

costs for upstream raw material and third-party marketing have squeezed profits, while low-quality and plagiarised goods have high return rates

Shenzhen has become China’s top CBEC hub, thanks to the Pearl River Delta’s strong manufacturing sector, active market entities and more lax regulations. It has easier access to capital markets and global industrial intelligence with its proximity to Hong Kong. With increasing numbers of CBEC players clustering in Shenzhen, the city has attracted a large pool of digital savvy trade professionals.

CBEC firms going global

Many outbound CBEC firms have struggled over the past one and a half years. Amazon’s fraud campaign, EU regulations on VAT and product safety and most recently, censure by PayPal for violations of third party payment rules, not to mention IP infringements, have caused immense pressure on an industry operating often with small margins.

Leading CBEC player Youkeshu 有棵树 had over 300 accounts shut down by Amazon. Tianze Information Co. 天泽信息, Youkeshu’s parent company, saw its revenue drop by 64 percent to C¥423 million in H1 2022 after a loss of C¥949 million in H1 2021. Other firms, such as Tongtuo Technology Co. 通拓科技, have been fined tens of million yuan by PayPal due to violations of platform rules and IP infringements.

On the contrary, a batch of CBEC firms who invested in product innovation and long-term brand-building survived regulatory scrutiny and sustained revenue growth, such as Lege Co. 乐歌股份. An intelligent furniture and office product company, Lege invested in its own overseas warehousing and logistics services, and offered space to nearly 400 other SMEs. The firm signed a shipbuilding contract with a capacity of 1,800 TEU in January 2022, with the ship expected to launch in March 2023. Operating its own container ship should enable Lege to navigate shipping price shocks.

Anke Innovation Co. 安克创新 invested some 7 percent of its revenues in R&D between January and September 2022, growing 40 percent y-o-y. Anke’s third-quarter profits grew by some 19 percent from last year, while Lege grew 8.6 percent in the same period.

Although a few leading CBEC players can scale up their R&D spending, still more, lacking funds, seem stuck at the bottom of global value chains. Lack of added value and rising local production costs is speeding up their exit from the market. Data indicate that a few publicly listed CBEC firms have reported a slight revenue recovery in H2 2022. At Q1 2023, the first full quarter since the PRC’s reopening, CBEC giants like Alibaba, JD.com and Vipshop all reported a modest increase in revenue. However, waning overseas demand amid global economic downturn and persisting inflation is expected to weigh on e-commerce exporters in future.

Temu, the global arm of PRC e-commerce giant Pinduoduo, has brought PRC-style budget shopping to the global market. It first launched in the US in September 2022 and in Australia and New Zealand in March 2023. Pledging free shipping, it arrived as consumers in advanced economies were bracing for hard times. It has spent heavily on advertising and social media, including a US$14 million Super Bowl ad and US$10 million in giveaway campaigns. Within seven months of its launch, Temu is already top among free apps in the US, ramping up 50 million installs since its launch in September 2022. Competitors SHEIN and Wish took three years to reach this milestone.

setting up independent website

CBEC independent digital sites steadily growing 2016-2021 (%)

source: iResearch

Independent websites, or the DTC (direct-to-customer) model, lets CBEC firms dodge third-party regulation, rising service fees and access restrictions on consumer data. The trend has slowly emerged since 2016 (see diagram). Responding to Amazon’s freeze on CBEC accounts from the PRC, Shenzhen’s Commerce Bureau convened affected firms in August 2021, urging them to create digital sites of their own to navigate third-party regulatory risk and offering funding support of up to C¥2 million for qualified projects.

As well as setting up their own, many firms are actively exploring new overseas sales platforms. According to MofCOM, PRC firms launched some 200,000 independent sites overseas in 2021. Nearly 30 percent of CBEC firms had by 2021 set up independent sites using domestic SaaS (software as a service) platform builders, such as SHOPLINE, reports the think tank Ebrun.

Independent sites help cultivate consumer loyalty, but brand building entails long-term commitment and advertising investment. SMEs struggle to find the staff and marketing skills to operate digital platforms. Many operate accounts on several platforms at once (Amazon, eBay et al.) to maximise exposure. Industry insiders urge this two-channel model on small players: they reinforce each other. Third-party sales platforms provide market feedback, advancing branding and making independent sites more attractive.

At one time, brands with independent sites often worked with social media influencers, a cost-effective way to spread good product reviews. The strategy is, however, now getting stale. Evolving into sites that aggregate and provide services for third-party sellers may be the ultimate manifestation of such independent sites as they grow in influence. Industry experts suggest this may be the case for SHEIN in the clothing sector (see case study).

case study: SHEIN

Founded in 2008 in Nanjing, SHEIN is now among the PRC’s most successful CBEC brands overseas. Downloads of SHEIN’s app skyrocketed following the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 and topped the ranking of iOS shopping apps in over 50 countries in 2021. Its annual revenue reached nearly $30 bn in 2022, with over 100 percent growth rates in the previous eight years. Its success comes from

- accurate market positioning

- targets females 18-35 who are avid fashion followers on limited budgets

- offers lower prices and more styles than competitors like ZARA and H&M

- low-cost and efficient marketing strategy

- attracts consumer traffic to its website via collaboration with social media influencers on Youtube, Facebook, Instagram and Tiktok

- interacts with customers on social media, encouraging them to share reviews and thoughts

- highly digitised market analytics and product selection process

- founded by Chris Xu with a background in IT, SHEIN has consumer algorithms in its genes; the firm can precisely predict fashion trends, track consumer activities and swiftly adjust product design

- rapid product iteration enabled by flexible supply chains

- its major competitor ZARA adds around 12,000 new styles per year; SHEIN adds 34,000 per week

- based in Guangzhou, China’s biggest apparel manufacturing centre, SHEIN has built up a network of over 300 resilient small manufacturers that can help with new product testing in small quantities (100). On average, ZARA would need at least 3,000 pieces produced for a new product to break even

- SHEIN shortens the cycle from production to delivery to 7 days, while the industry average is two weeks

- extended supply chains in logistics

- SHEIN is one of the earliest buyers of overseas warehousing among PRC CBEC firms. It has outperformed ZARA in controlling logistics costs

building overseas warehouses

Overseas warehouses are allowing CBEC firms greater cost control over shipping, and faster delivery times. Localities are rolling out millions in subsidies, above all in coastal provinces. Between 2019 and 2021 overseas warehouses owned by PRC firms doubled to 2000, reports MofCOM. The Shenzhen Cross-Border E-Commerce Association reports around 250 overseas warehouses were operated by CBEC firms registered in Shenzhen by the end of 2022, with the total area ranked no.2 nationwide.

With storage overseas, shipments can anticipate holidays when mass orders are placed and containers are in high demand. Products can be grouped in single bulk shipments, streamlining customs clearance and curbing logistics fees. More to the point, locating warehouses in regional transport hubs enables flexible exchange and return services.

As PRC CBEC platform giants, most notably AliExpress (case study), go global in emerging markets, small B2C sellers hope to take advantage of their customised logistics services to reach local customers.

case study: AliExpress

Launched by Alibaba Group in 2010, AliExpress has ventured into Eastern Europe, Latin America and Southeast Asia over the past decade, with Russia standing out as its largest overseas market. It has established partnerships with Russian social media websites and telecoms firms to localise marketing and product promotion.

- Alibaba logistics arm Cainiao now has warehouses in countries including Russia, Spain, France and Poland, localising delivery, reducing shipping costs and cutting delivery times.

- growth of AliExpress’s services benefits from Alibaba’s powerful consumer algorithms, empowered by AI, big data analysis and cloud computing, providing tailored product suggestions to local customers and cross-border payment solutions per Ant Financial.

- SMEs selling overseas via AliExpress can leverage its consumer analytics

Alibaba helps rule-setting for global CBEC via its eWTP (Electronic World Trade Platform) initiative (2016), promoting public-private dialogue.

Global demand for overseas warehouses, however, has waned since the second half of 2022 due to falling consumer spending and shipping fees. According to Wang Xin 王馨 Shenzhen Cross-Border E-Commerce Association (see profile), this has left a large number of overseas warehouses idle, with high empty rates in 2023.

Overseas warehouses costs have more than doubled since pre-pandemic times. The annual rental for a 10,000 square metre warehouse in Los Angeles was around US$10 million in 2020, but US$300-400 million by the end of 2022, a higher than ever entry threshold. Expansion is further dampened by the 2-3 year profit cycle. Qu Rengang 曲仁岗 Disifang’s (China’s leading export and import logistics firm) overseas warehouse business notes that in the next 3-5 years, overseas warehouses would seek to transform from general storage to brands or goods-specific storage. Qu urges more transparent industrial standards for overseas warehouse operation, for more regulated sectoral growth.

Lege Co. 乐歌股份, one of few PRC CBEC players invested in their own global logistics system, has been consolidating its 15 overseas warehouses to improve operational costs per square metre. Xiang Lehong 项乐宏 Lege’s chairman remains optimistic, referring to US manufacturing’s reshoring strategy and preference for local assembly.

risks affecting two-way CBEC sellers

regulatory compliance and IP protection (see Feng Xiaopeng profile)

Global regulatory scrutiny—not least of PRC violation of intellectual property rights—is now a key risk for its CBEC suppliers. The need for legal assistance has created an entire industry chain. Trademark and copyright infringement has been a two-way issue, with many Chinese SMEs plagiarising foreign products while overseas sellers copy certain PRC-designed products. Firms are urged to make full use of third-party legal services, such as those provided by AliExpress, for their own protection. Heatedly discussed in WTO and regional negotiations, greater coordination in cracking down on cross-border IP fraud is on the cards.

Meanwhile, as overseas regulators tighten up anti-monopoly scrutiny of platform giants, PRC sellers face rule changes offering tempting returns yet entailing greater compliance. Top-notch independent players, like SHEIN, may also be subject to information and algorithm disclosure outside the PRC.

Trading firms need to understand IP protection rules of target markets and arrange appropriate risk management plans. For instance, firms need to be extra cautious with technology- and IP-intensive products at the product selection stage. They can require suppliers to provide copies of IP ownership proof and archive those to protect against risks of future IP disputes. Firms can also submit IP applications in local markets and file their records to PRC customs for border protection. When facing overseas IP lawsuits, SMEs should use professional legal service providers for help to avoid unnecessary penalties or huge fines

Feng Xiaopeng 冯晓鹏

King & Wood Mallesons partner

cross-border data regulations

Beijing’s desire for more voice in global rulemaking for digital trade is displayed in its 2021 bids to join

- CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership)

- DEPA (Digital Economic Partnership Agreement).

Far-reaching restrictions on cross-border data flows under Beijing’s Cybersecurity and Data Security laws require foreign data localisation across industries to assuage Beijing’s security concerns and to support PRC national champions. Aligning with the US model, on the contrary, DEPA urges seamless data and information transmission among signatories, in line with their commitments to the CPTPP that favours an open global digital market benefiting multinational tech giants.

The lack of a set of unified global regulatory standards on cross-border data flows generated through digital services trade has posed data security risks to CBEC firms and third-party platforms. Despite negotiations under the WTO framework, progress and consensus on CBEC are not helped by systemic hiccups and data incompatibilities. Digital trade rules, e.g., digital taxation, also have some way to go.

The flexible accession protocols encourage Beijing to seek common ground in dealings with DEPA members on traditional business and trade topics before attaching chapters on data issues. Beijing remains adamant on data localisation, but more ‘give’ may occur in the rollout, luring high-tech international investment and easing external R&D exchanges, through which PRC tech SMEs stand to benefit from global collaboration and market competition. Lengthy chapters on digital trade facilitation—e.g. paperless customs procedure and online transaction systems—are hoped to open new markets for CBEC firms expanding overseas.

looking forward: emerging markets and RCEP

CBEC giants like Alibaba, Tencent and JD.com, and e-commerce players Tiktok and Xiaohongshu, have grown their footprints in emerging markets, especially Southeast Asia. Here, they profit from booming local digital economies and young populations. According to a 2022 report on the region’s digital economy jointly released by Google, Temasek and Bain, total Southeast Asian e-commerce transaction volume reached US$131 billion in 2022, growing by 16 percent y-o-y, and expected to reach US$211 billion by 2025.

Intense competition among local and PRC e-commerce platforms is crowding the ASEAN market, but logistics services still present a huge potential. JD.com may have shut down its e-commerce businesses in Indonesia and Thailand at the beginning of 2023, but its local storage and logistics arm remains active. Alibaba’s presence in ASEAN is run by AliExpress and Lazada, a local e-commerce platform acquired by Alibaba in 2016, with a local delivery network. Currently, Cainiao Logistics and Lazada co-run over 400,000 square metres of bonded warehouses covering six ASEAN countries.

The lack of adequate transport infrastructure, modern digital payment methods and a skilled labour force are outstanding challenges facing PRC e-commerce logistics expansion in Southeast Asia.

On the other hand, RCEP (Regional Economic Partnership Agreement) that came into force in January 2022, presents Chinese CBEC firms with new opportunities in China-ASEAN trade

- reduced tariffs on imported raw materials and intermediate goods

- unified rules of origin, customs procedure, quarantine and inspection requirements and technical standards, etc.

- streamlined cross-border logistics via simplified customs clearance and authorised economic operator (AEO) mutual recognition; will face little competition from nascent local logistics industries

- comprehensive IP regulations and dispute settlement mechanisms

In addition, emerging markets in Latin America, Middle East and Southeast Asia, such as Brazil, Mexico, Gulf countries, Kenya, etc, have been targeted by PRC e-commerce giants and logistics firms as the next growth points. Jitu Express 极兔速递, China’s top express delivery firm, set up in Brazil in May 2022. Its international services network offers customs clearance storage and ‘last mile’ delivery services to Chinese CBEC sellers with independent websites.

E-commerce has streamlined, digitised and personalised cross-border transactions. If done well, this should ensure direct and faster global delivery of tailored products from the PRC. If local regulation allows, sellers’ own websites and PRC-run overseas warehouses should underpin trade with PRC brands that will become ubiquitous in some markets. PRC agencies wholeheartedly support the sector’s growth in emerging markets, above all in Southeast Asia, where RCEP is cutting transaction red tape.

Beijing is stepping up its ambitions to lead the drafting of global digital services trade rules, recognising they are critical to the longterm sustainability of the CBEC industry. But shrinking global demand and an increasingly political trade environment are challenging business strategies. Transforming from a quantity to a quality and innovation business model is ever more urgent in an overcrowded and costly sector. IP infringements remain conspicuous. PRC firms need to raise their game in compliance, standards, and risk, to hold onto e-commerce markets.

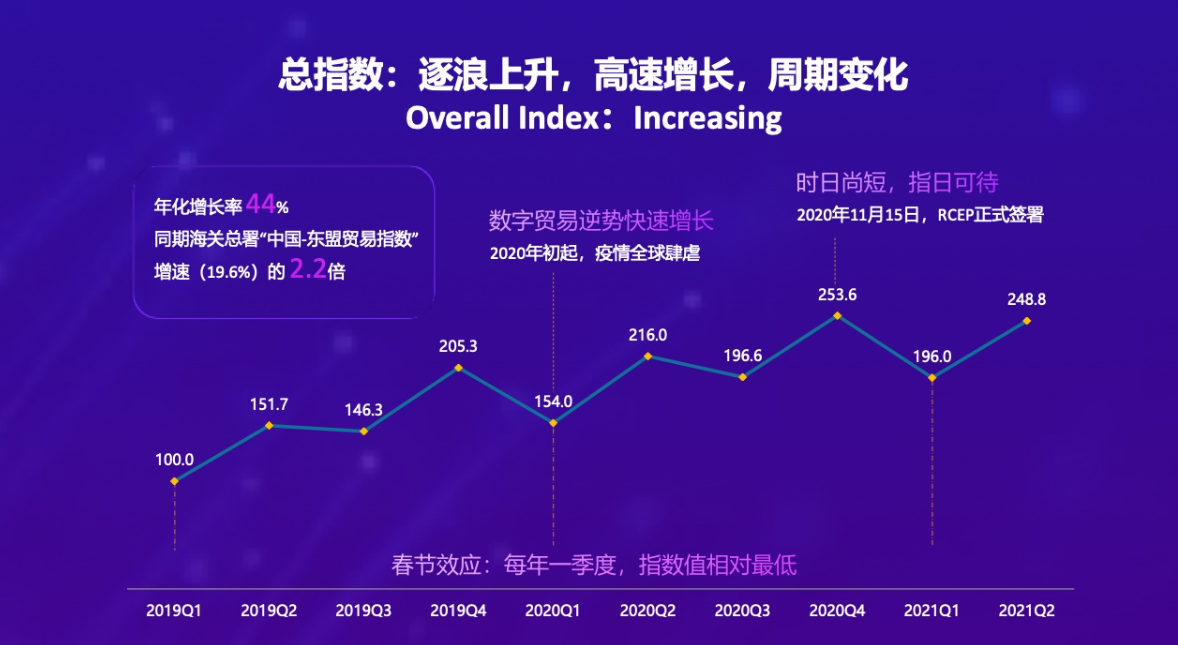

Index rising for RCEP regional imports

RCEP regional CBEC import (B2C) index

A first RCEP regional CBEC import (B2C) index was issued at the Second China International Consumer Goods Fair, held in Hainan in July 2022. Co-authored by Zhejiang University, Alibaba Research Institute and Tmall International, the index includes

- four first-level indicators

- trade volume

- corporate development

- market demand

- consumer experience

- nine second-level indicators

- 11 third-level indicators

The index illustrates a rapidly growing pattern with cyclical adjustments. The overall index has nearly doubled from 2019 to Q2 2022; annual growth was 33.2 percent over 2019-21. Among the four first-level indicators, ‘trade volume’, the CBEC import volume of RCEP members, has risen fastest—some 44 percent. CBEC firms and brands keep proliferating, signalling the health of digital trade among members. The huge PRC consumer market is attracting exports to the PRC.