The ways in which PRC food consumption trends are being shaped by urbanisation, income growth and global repositioning are examined in this China Executive Briefing. Fast-evolving CBEC regulation is opening the market for high-end international exports; Beijing’s mantra of self-sufficiency in basic commodities remains aspirational.

Introduction

Consumer food tastes across the PRC are changing. Rising incomes underpin a switch from quantity to concerns for nutrition and safety, and a leap in demand for better quality and greater choice. Yet se-verely strained land and water resources challenge production, just as persistent food safety dramas worry middle-class consumers. While markets for high-end products are certainly opening, Beijing deems self-sufficiency in key food grains—rice and wheat—foundational for food security.

China Executive Briefing | The Future of Australian Agriculture in China

March 1, 2022 — Scott Waldron, associate professor at the University of Queensland’s School of Agriculture and Food Sciences; Michaela Boehme, research manager and lead analyst at China Policy; and Patrick Hutchinson, chief executive officer at the Australian Meat Industry Council, discuss the future of agriculture and trade between Australia and China in light of the ongoing dispute between the two countries. The participants examined the implications of China’s import restrictions on Australia’s food exporters, how it affects China’s own food policy, and lessons learned moving forward. Dr. Courtney J. Fung, associate professor at Macquarie University’s Department of Security Studies and Criminology, moderated the discussion. (54 min., 55 sec.)

Food security

Never far beneath the surface for Beijing, food security rocketed up the agenda in 2020–21 as extreme weather collided with COVID-led volatility in domestic and global agrifood markets. Mostly kept under tight control, grain imports took off in 2020, jumping by 18 percent y-o-y in 2021. They show few signs of falling back to pre-pandemic levels. Mounting demand for animal feed to boost meat and dairy production is the main driver of demand.

Over-hyped official self-sufficiency targets for bulk commodities are at odds with scholarly and industry estimates (chart 1). For all the mounting emphasis on ag production, domestic supplies will fail to satisfy demand. In core commodities like wheat, rice and corn, a few percent change in PRC production (the biggest in the world) can create massive shifts in global grain trade.

chart 1: self-sufficiency rate by key commodity, 2021 vs 2035

(percentage share of domestic production in total supply)

source: National Bureau of Statistics, estimation made by ag economists

Ding Gangqiang 丁钢强

Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Nutrition and Health director

In recent decades of high growth, Chinese diets have become energy-dense, with a high intake of refined grains, fat, sugar and salt, Ding points out. These bring with them chronic disease and micronutrient deficiency. Food manufacturers that invest in R&D for healthy products will be winners in future agrifood markets, he predicts.

changing diets

Urbanisation has supported double-digit growth in recent decades. Some 80 percent of the population lived in rural areas in 1980; by 2021 just 35 percent. The shift brought rising incomes and a well-off middle class; diets changed from grain-based to more diverse and protein-rich.

The meaning of food security has been reconfigured by this shift. It used to mean enough grain for everyone. Now meat and fresh produce are taken for granted as part of a nutritious ‘quality diet’. China’s traditional thinking insists that a stable state rests on the rice bowls of common folk. This bind has never been broken, but the bowls now contain a large variety of foods.

Representing the state’s tacit endorsement of certain nutritional patterns, the National Dietary Guidelines, released by the China Nutrition Society, have been revised several times. The traditional (and still current) carbohydrate-heavy diet is to graduate to a blend of cereals, meats, vegetables, fruit, milk and soy (chart 2).

chart 2: recommended annual per capita food intake in the 2016 National Dietary Guidelines and actual intake in 2020 (kg per capita)

sources: China Nutrition Society, National Bureau of Statistics, Life Times

the COVID effect

The share of consumption in the PRC economy, while still far below that of advanced countries, has risen over the last decade. China’s final consumption as part of GDP was 48.9 percent in 2010; it peaked at 56 percent in 2019 before falling in 2020, according to the World Bank. COVID-19 has stifled overall confidence. In the 2020 ‘Consumer borrowing attitude survey’, close to half the respondents intended to live more frugally and seek value for money when selecting products, while 36 percent were willing to spend more for products of higher quality.

This impacts food consumption. Another survey reveals that consumers intend to buy healthier food and fresh produce (chart 3). Wealthier but cautious consumers may trigger structural changes in the food market.

chart 3: changes in consumption during the spring 2020 pandemic outbreak

(percentage proportion of consumers reporting increased minus those who cut consumption)

sources: Netease and EZ-Tracking, 2020

eating for health and convenience

Demand for meat, dairy and fresh produce grew during the pandemic. In 2020 local consumption of milk rose by 16 percent y-o-y, reaching a 15-year peak, reveals China Nutrition Society data. Organic soybean products grew more than fourfold. Imports of health foods reported record highs, up by 11 percent y-o-y.

COVID-19 has caused mass lockdowns nationwide, forcing people to stay in and prepare meals at home. Concerns about catching COVID in public venues has further discouraged eating out. Restaurants have adapted, switching to prepared meals that customers can take home, giving them greater choice.

Pandemic-led changes are short term, but there is also a profound demographic change: the population of single adults surpassed 260 million by 2019; 70 million live alone, a ready market for convenient, small-portion meals.

the business potential of ready meals

The market for ready meals, to be eaten directly or with minimal cooking, is taking off. The market volume was estimated at C¥200 bn in 2021, and will likely reach C¥600 bn by 2025. Global ag suppliers may find chances to work with downstream domestic restaurants or ready meal companies.

Rogue players using low-quality raw ingredients have caused food quality and safety scandals. High-end pro-ducers and their customers want safe and stable supply chains that deliver quality ingredients; this is a growing market for global exports to the PRC’s ready meal market.

Weizhixiang 味知香 is the pioneer and top player in China’s ready meal in-dustry. It stresses the quality of its raw ingredients: some of its beef short ribs are from Australia and New Zealand, some shrimp from South America, and some pork from Spain.

further moving online

Prior to COVID-19, PRC consumers were already among the world’s most online, accounting for some half of global e-commerce sales. In 2019, the last year for which ag CBEC (cross-border e-commerce) figures have been issued, Australia held the largest share of the PRC market.

Online shopping increased when the virus struck. Surfing this wave, e-groceries recorded 29 percent y-o-y growth in 2020. Nationwide CBEC distributors, already taking shape pre-pandemic, received further boosts from measures to incorporate more regions; cold-chain logistics networks benefitted above all.

CBEC: cushioning Australia-China ag trade

Cross-border e-commerce is booming. For all the friction between Canberra and Beijing, Australian exporters have felt only minor disruption. Australian food exporters with a reputa-tion for quality and safety stand to gain from growing demand for consumer choice. Mean-while, COVID-19 has reinforced the importance of traceability, offering additional opportuni-ties for international brands that can provide consumers with information on their products’ journey from farm to table.

Premium Australian CBEC exports—infant formula, dairy products, packaged snacks and health foods—are still doing well.

Beijing is likely to continue to support CBEC: the positive list for imports is getting longer. Frozen seafood and alcoholic beverages were added in 2020, potentially opening new mar-kets to Australian industry.

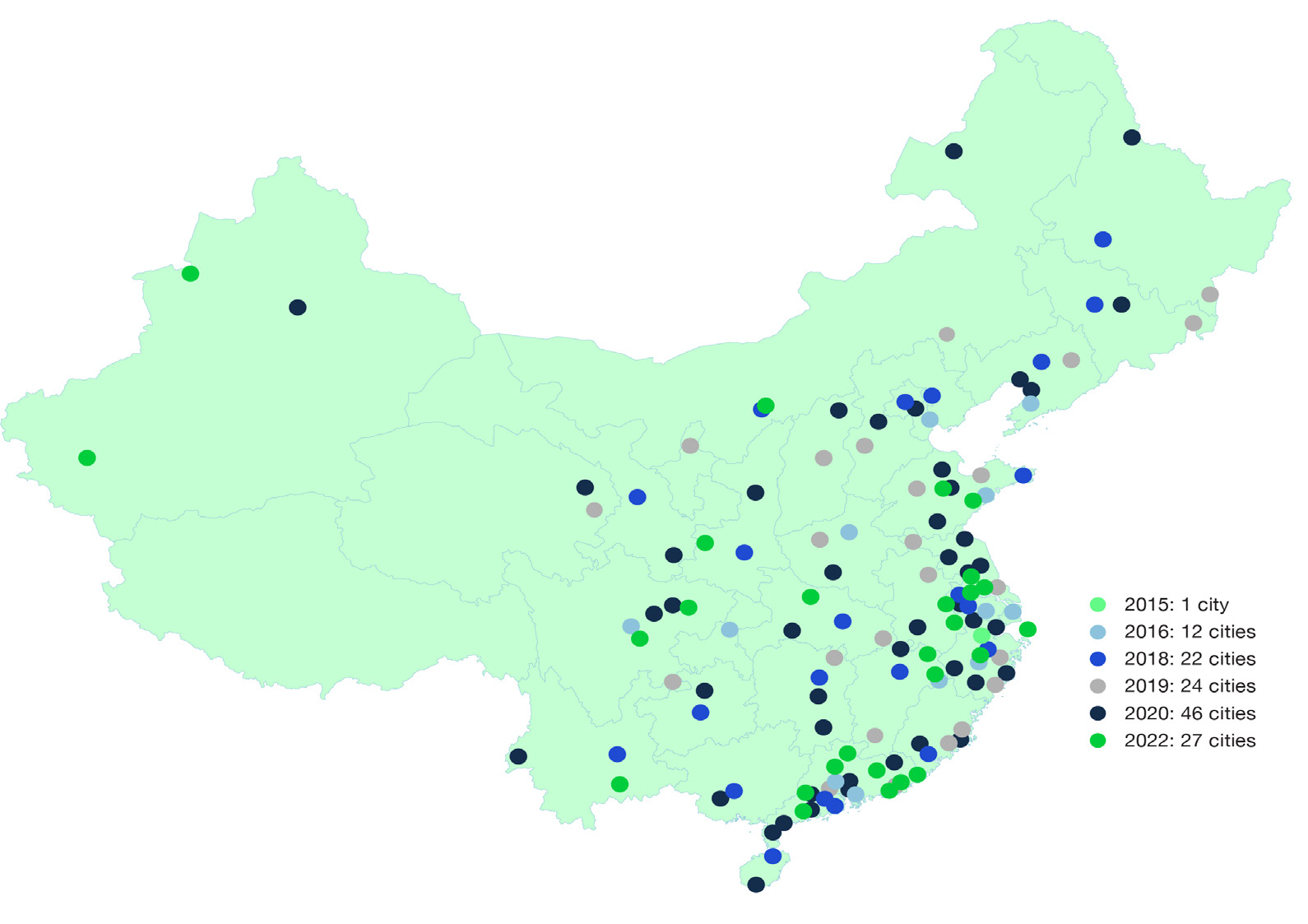

A massive proliferation of CBEC pilot zones (map 1) is expanding access to smaller cities and regional markets, where the fastest growth of demand is now taking place. Previously deemed too remote for high-end food imports, tier 3 and 4 cities are new arenas for CBEC rivals; all are aggressively expanding their coverage while working to resolve logistics and supply chain issues.

Given Beijing’s fear that refrigerated food is a COVID vector, improving cold chain capacity has become a policy priority. For imports, this entails tighter regulation and onerous compli-ance requirements. Shrill warnings to consumers to avoid imported cold chain foods implies risk to exporters selling high-quality food products. Better cold chain logistics across the PRC will nonetheless, in the long run, be a plus for exporters.

map 1: CBEC pilot zones, 2015–22

Community group buying, live streaming, short videos on social media and other emerging online sales vectors have followed the trend. Coupled with demand for quality and choice, this opens doors for international suppliers, who may find it easier to reach larger groups of Chinese consumers through CBEC (chart 4).

chart 4: ag CBEC market shares, 2019

source: Farmers’ Daily

Policymakers, facing mounting food import pressures, are urged by Chen to break with the conventional equation of importing food and buying from the ‘ABCD’ firms (i.e. Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus). Targeted investment should build infrastructure in exporting countries. Logistics hubs, storage, ports and processing plants would be part of stable partnerships with overseas grain producers, assuring them of long-term agribusiness and China of a broader range of ag trade partners.

Deeper involvement in local production via investment and tech transfer provides additional soft power, adds Chen. Domestic supplies and shrinking national reserves need to be complemented with imports, but this must be done smartly to create a ‘win-win’ situation with exporters.

Chen Xiwen 陈锡文

National People’s Congress Ag and Rural Affairs Committee chair

protein demand shaping commodity trade

With the domestic ag sector losing competitiveness vis-à-vis global producers, Beijing’s issue is no longer whether to source essentials abroad, but to determine what is essential and how to maintain supply chains on its own terms.

Major agrifood suppliers are carefully watching Beijing’s moves to encourage a broader range of trade partners; the aim is to foster global agribusiness partners to compete with established global players. Standoffs with leading exporters, including Australia and Canada, have added momentum to Beijing’s quest. BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) countries stand to benefit, above all those in central Asia, eastern and central Europe, and Russia.

Diversifying suppliers, however, is easier said than done. In principle, Beijing can mandate targets at home, pushing domestic production until it hits its resource constraints, but bringing on more suppliers requires patience and long-term investment. Many BRI countries are politically and socially fractured. Investment in them carries significant risk. With limited production capacity, emerging partners have yet to threaten leading exporters whose bulk commodities and quality produce are still valued by PRC buyers.

opportunities for high-end and feed grains

The state’s stance on self-sufficiency in food grains varies by crop. Imports of staple grains (wheat and rice) are tightly controlled; minor crops, long overlooked by regulators, face fierce competition from efficient global suppliers.

wheat

Domestic wheat production, long concerned only with output, has ignored seed quality. Imports, largely for specialised use, fill the gap. For instance, Australian wheat, primarily used in bakery products and high-end Asian food, is acclaimed for its quality and green credentials.

Bilateral friction has failed to dint China’s appetite for Australian wheat. Australia is expecting a second consecutive bumper harvest, while northern hemisphere producers have been hit by bad weather and drought. At least 265,000 tonnes were shipped from Australia in June 2021, taking its total wheat exports to China to about 1.7 million tonnes for the 2020/21 marketing year. This was 22 percent higher than the volume China took for the full 2019/20 marketing year, making Australia its third-largest wheat exporter (following Canada and the US).

barley

Over 90 percent of China’s barley supply is shipped in. Prior to anti-dumping measures against Australian barley, it dominated PRC imports. Supply was stable and cheaper than domestic grain. The malting industry consumes 3 million tonnes of barley annually; in 2019 over 60 percent was from Australia, which has won itself a reputation among beer producers, including big players like Tsingtao Beer. With little hope of local supply catching up, Australia’s global competitors have quickly filled the vacuum. In 2020, Australia still accounted for some 20 percent of the PRC market; the share was fully absorbed by Canada, Ukraine, France and Argentina in 2021. When relations warm, Australian barley will likely return to a strong market position; this will, however, be in a more diverse group of suppliers, as Australia itself diversifies its markets.

Demand for cheaper alternative feed is also driving imports, bypassing Beijing’s issues with Australia. PRC feed producers have increased the proportion of wheat and barley in their formulae since 2020, following instructions to reduce reliance on expensive corn and soymeal. Given its booming livestock sector, imported wheat and barley have started to flood China’s market. The current price of Australian wheat makes it irresistible to Chinese buyers; barley is sourced elsewhere.

rising popularity of baked goods

The majority of domestic wheat has mid-range gluten levels, producing flour suitable for traditional Chinese noodles and steamed bread, which dominate consumption. However, growing demand for Western-style baked goods means flour with both higher and lower gluten levels is required for breads and cakes respectively.

The baked goods market is estimated to have reached some C¥300 bn in 2021, still with room for improvement. China’s annual per capita consumption of baked products was 7.8 kg in 2019, far below that of Western countries (US: 43.1 kg; France: 75.8 kg). It was low even compared to Asian countries with broadly similar dietary patterns (Japan: 22.3 kg; Singapore: 17.9 kg). Annual demand for high-quality wheat has been around 10 million tonnes in recent years; domestic output provides 5–6 million tonnes, leaving a 3 million tonne gap that is filled with imports.

fibre: the state of wool and cotton imports

Wool is unchallenged: exports cannot be substituted from other sources and are not deemed strategic by Beijing. The preferential import quota rose in both 2020 and 2021. Cotton shipments to the PRC, clearly strategic, have declined severely. They now head for Vietnam, Indonesia and other textile processing centres.

meat consumption: options beyond pork

Livestock farming is moving up the agenda as meat consumption continues to rise. The share of pork production fell 10 percentage points during 2017–20. Beef’s status as a healthy protein and the popularity of steakhouses and world food have spurred demand, while resource constraints limit the growth of local supply. Imports are set to increase. Breeding better herds, standardising inputs and zero tolerance of disease are vital if a strong livestock husbandry sector is to be built. But the goal of 85 percent self-sufficiency by 2025 is aspirational.

beef

Australian beef is considered ‘world-class’ given its clean environment for livestock, modern management and quality control. The majority (55–70 percent) of Australian beef consumed in China is in Western-style dishes, according to data from Meat and Livestock Australia and surveys on beef cut uses.

seafood

Seafood, considered a high-quality protein, has surged in popularity in recent years, now accounting for 30 percent of animal protein consumed, up from 23 percent in 2005. In H1 2021, when the pandemic was temporarily under control and the fear of COVID transmission through cold chains was less acute, seafood sales surged by 283 percent in comparison to 2019.

The market still has potential. The national average daily intake of seafood is 24.3 grams, low by international standards, and should rise to 40 grams, research suggests. Seafood-based products, including staple foods, pre-cooked meals and snacks, are also emerging options. With more purchasing power, consumers are creating opportunities for imported high-end products including lobster, king crab, salmon, scallops, tuna and silver cod.

chart 5: beef imports by country, 2020

source: General Administration of Customs

PRC markets took some 95 percent of Australian lobsters in 2018–19. The boom ended when Beijing–Canberra friction in late 2020 led to unofficial trade barriers for Australian products. Still highly valued in China, lobsters reached the market via grey channels through Hong Kong. Monthly shipments to Hong Kong spiked from January 2021 on, from 100 tonnes per month to 250. A large share of the increased import undoubtedly entered the mainland market illegally.

This became a national security concern, triggering joint law enforcement action between Hong Kong and mainland authorities. In September 2021, a Hong Kong marine police officer was killed during an attempt to intercept a turbocharged speedboat taking lobsters into PRC waters.

surging smuggling indicates popularity of Australian lobster

reputation surviving and thriving

Chinese consumers will continue to demand a broad range of high-quality ag products. Beijing, intent on reducing dependency, must source these from a greater number of global suppliers.

Ag commodity trade with China remains a challenge. In the short term, openings—while niche—are emerging in healthy, more convenient and functional foods and beverages. In the mid term, growing access to

a national consumer base via fast internet, sophisticated e-platforms and better logistics will allow exporters to focus on the end consumer. Australia’s reputation for quality produce survives and thrives. Preference for imports at the high end of the market is as true for food as it is for handbags.

import windows opening, but compliance tightening

RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), a trade pact bringing together 15 Indo-Pacific countries including China and Australia, came into force on 1 Jan 2022. The pact will enrich the range of ag imports into the PRC, delivering beef, lamb and dairy products from Australia and New Zealand and tropical fruit from ASEAN to PRC consumers.

Chinese investors in ag production and processing will benefit from greater opportunities in Asian countries. Most are also BRI members, hence already in the PRC’s sphere of influence and preferred traders. Beijing is looking for more compliant supply chains directly based in exporting countries that will help secure food supplies.

Preferential rules in the RCEP agreement will gradually roll out, yet benefits for food exporters will be uneven. Countries already enjoying advantageous tariff rates from bilateral trade agreements with China will find RCEP has less of an impact on their trade with the PRC. Under ChAFTA (China–Australia Free Trade Agreement), for instance, import tariffs for key ag product categories such as milk powder or chilled and frozen beef are currently lower than the tariff commitments enshrined in RCEP.

Exporters to the PRC also face stepped-up compliance risks due to customs decrees 248 and 249. Clarification issued in November–December 2021 came too late for exporters to upgrade their supply chains ahead of the 1 January deadline. Requests from trade partners for a grace period were dismissed. Food exporters will struggle to comply with the stringent rules, e.g. on cold-chain security. Industries foresee chaos through Q1 2022.