This brief examines China’s post-COVID ‘New Era’ health policy trends and opportunities for Australia.

Introduction

Across the domestic healthcare sector, Beijing is pivoting to home-grown drugs and R&D. Concerns for COVID, amid deglobalisation and the threat of ‘foreign hostile forces’, see the sector top the non-traditional security list. COVID is still disrupting the sector, but healthcare supply security is moving up the agenda; meanwhile, well-planned reforms underpin an anticipated ‘New Era’ of healthcare. This is to be ensured in the long run from strictly local resources. Global partners are still welcome but must navigate a hard-nosed single state buyer that is challenging domestic and global pharma alike.

Safeguarding domestic health and aged care in the face of volatility will top the PRC’s post-COVID health agenda. On edge about its ageing population, Beijing is shielding the domestic health industry from a legion of external risks by

- centralising procurement to promote domestically produced generics

- denying foreign researchers access to PRC citizens medical data

- favouring PRC firms in telemedicine, a highlight of ‘Healthy China 2030’

- squeezing global pharma on drug/medical device prices and joint trials, in exchange for timely approvals and/or procurement

Insistence on zero-COVID has, for the time being, derailed health sector restructuring and disrupted plans to make supplies more secure. Reforms, nonetheless continue; Beijing’s clear list of priorities cover

- universal healthcare: a multi-tier system is being put in place; the basics ensured by the state and the rest covered by private and community bodies

- drug affordability: central procurement is radically reconfiguring pricing, reducing market clout for local and global pharma and equipment firms

- hospital system restructure: as single-buyer insurance gains market share, service providers, not least public hospitals and multi-tiered grassroots bodies, are next to be streamlined

- improved aged care: a blueprint for affordable, accessible care is taking shape amid rapid population ageing

- pro-natal policy: more than removing barriers to a third child, it includes housing, education and maternal and child care

Taken together, these steps underpin a hoped for ‘New Era’ of health and aged care provided from strictly local resources. The PRC remains keen to engage with the global community on whose experience and skills a successful transition depends, but it now also demands to do so on its own terms.

International providers must pull off a delicate balancing act of their own: working more closely with PRC counterparts, they must firewall their operations to ease security fears mounting in their home countries.

China Executive Briefing | Engaging China on Health Policy

July 21, 2022 — A panel of experts unpacks the future of China’s health policy, its major health trends, and evolving social and health challenges. Participants include Peking University’s Institute for Global Health and Development Dean Gordon G. Liu, Cochlear Medical Affairs Vice President Dr. Dell Kingsford Smith, and The George Institute Honorary Senior Fellow Dr. Maoyi Tian. China Policy Managing Director Philippa Jones moderated the conversation. (52 min., 48 sec.)

zero-COVID minefield

But COVID management, for the time being, remain a stumbling block for all players. Zero-COVID cannot be questioned, insists the Politburo—regardless of the impact on the economy. Facing an ever louder public, the Party threatens any voice that ‘distorts, questions, or denies’ the policy. Beijing Party Secretary Cai Qi 蔡奇 declared on 27 June that COVID control would be in place for the next five years. The online backlash, underscoring the level of public frustration, saw the remarks erased from the internet within hours.

Zero-COVID remains the formal edict. But Beijing has quietly retreated from eradication. There are now four degrees of zero, more may emerge

- stage I: ‘zero COVID cases’ 零感染 no recorded cases in a given region during a given period

- stage II: ‘erasing COVID cases’ 清零 trace and quarantine all positive cases and their close contacts until they test negative twice in a row

- stage III: ‘dynamic zero-COVID’ 动态清零 understand chain of infection, contain flare-ups through rapid targeted actions

- stage IV: ‘zero-COVID at the level of society as a whole’ 社会面清零 flatten the epidemic curve as quickly as possible

Zheng Bingwen 郑秉文

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Centre for International Social Security Studies director

During the 14th 5-year plan, over 20 percent of the PRC, some 300 million people, will be over 60; the birth rate will fall below 0.01 percent. Ensuring robust and independent long-term care scheme is crucial. Population ageing will, he warns, pile pressure on social insurance, employment, budgets and economic growth. Decisive measures will be needed.

struggling for a post-COVID rebound

game plan for the rapidly-ageing society

The landmark Basic Health and Healthcare Promotion Law, passed in 2019, enshrines healthcare as a right. A sweeping framework, it marks a conceptual shift from reactively treating disease to proactive health management, including improving lifestyles, multi-level care and care for the elderly.

The blueprint envisages a multi-tier system dispensing universal healthcare. The state ensures the essentials; private and community agencies cover the rest. Service provision will be restructured when the nascent single-buyer Basic Medical Insurance (BMI) scheme has confident control over product markets.

In over 20 cities, mostly on the east coast, over 20 percent of the population is now 60 or above. This rapid ageing of the urban population has put the sustainability of the state insurance fund at risk. Moreover, disease patterns have shifted with changing lifestyles: cardiovascular disease and diabetes rates are spiking; mental illness rates are also rising rapidly, with new data showing over 100 million people suffer from some form of depression.

Uneven distribution of resources makes healthcare services inaccessible to many. The vast majority of the 2,000 tertiary hospitals are concentrated in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and other first tier cities; the bulk of their patients are non-locals who cannot find proper treatment closer to home.

Major upgrades to public health were prompted by the SARS epidemic in 2002. The COVID-19 crisis revealed that much of the rhetoric had not been followed through. Investment is again imperative, but funds, it is feared, will go to tech rather than the needed investment in public health skills and services.

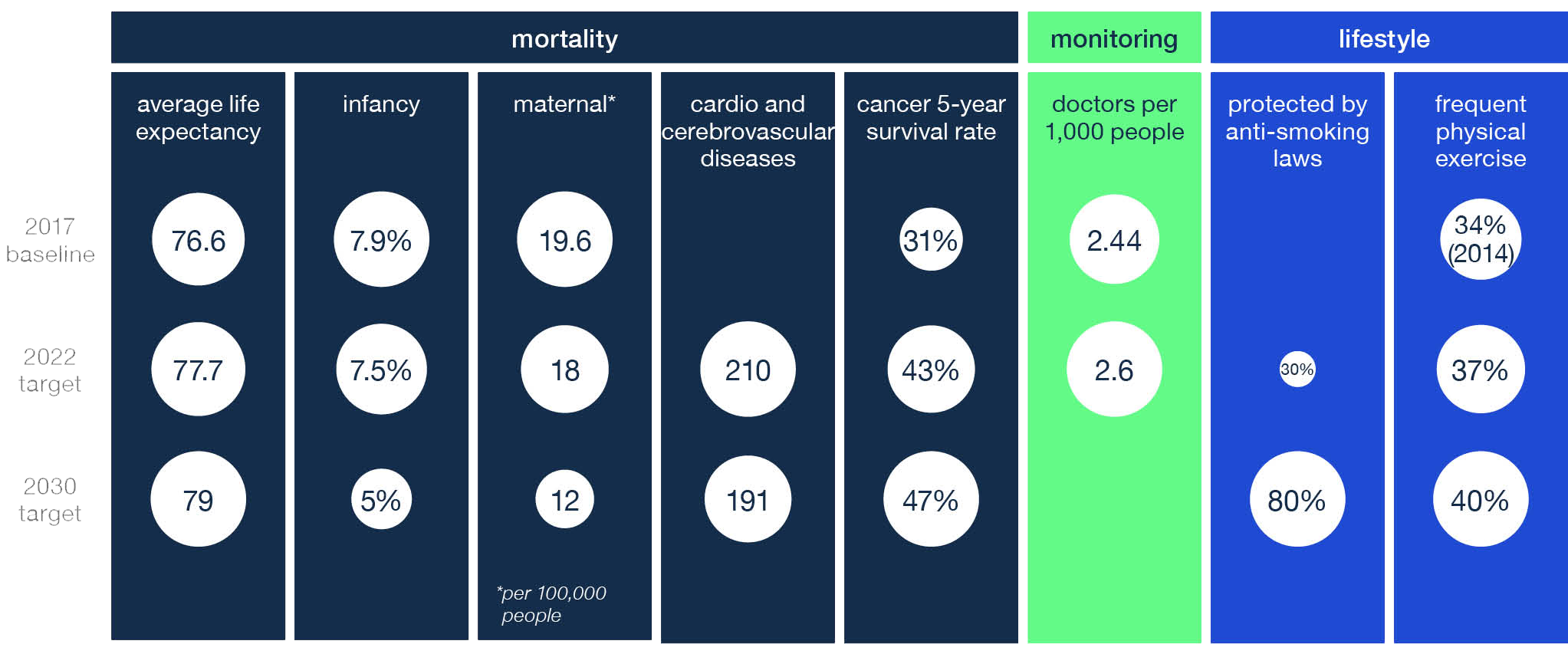

chart 1: Healthy China 2030 to shape health tech development

source: National Health Commission, National Bureau of Statistics

shortage of care and care providers

COVID lockdowns are an ever present fear nationwide. With ballooning numbers and severe infections claimed to be ‘miraculously few’, large cities including Shenzhen, Beijing and Shanghai are imposing ‘dynamic zero-COVID’, with residents thrown in and out of lockdown. Medical care is struggling—if not failing—to balance COVID demands with treatment of acute and chronic disease. Many tragic stories are emerging, including of patients unable to access dialysis and other life saving treatments.

Massive investment in public health infrastructure is in train, with the state building infectious disease hospitals and advanced biosecurity labs, and mandating reserves of emergency medical supplies. Flagging the current sorry state of stocks, urban development plans since May 2021 never fail to mention shoring up health infrastructure. Demand for medical equipment is tipped to rise. Yet the obsession with infrastructure draws criticism from medical experts. To fend off the next epidemic, low pay for healthcare workers and inadequate grassroots hospitals should be corrected, they point out.

To improve healthcare in a relatively poor county, a pilot was kicked off in Sanming in 2013. Led by Zhan Jifu 詹积富, then chief of Sanming Food and Drug Bureau, the experiment featured ‘synergy among drug procurement, care provision and care payment’. It experimented with the PRC’s first ‘collective and centralised procurement’, which effectively cut drug kickbacks and increased supply. The Sanming Model was endorsed by Beijing and essentially created the blueprint for NHSA-led national healthcare reforms since 2018. Zhan was promoted to head of healthcare security of Fujian in 2018 and then head of Sanming People’s Congress in 2019.

healthcare pilot reform in San-ming, Fujian 三明医改

slashing drug prices

strengthening insurance bargaining power

A new round of healthcare reforms was launched in 2019, focusing on three areas: insurance, drug rationalisation and coordinated services.

Early stages saw efforts to extend BMI (Basic Medical Insurance) to all citizens. A basic medical insurance scheme had been launched in cities in the late 1990s, when state employees lost access to company benefits amid state-owned enterprise reform. It has been gradually extending to other population groups.

The NHSA (National Healthcare Security Administration) was formed in 2018 to manage the current BMI fund. Overpriced drugs were targeted as culprits in fund shortages. Their prices were failing to drop when patent protection ended, and local generics proved less effective than their originals.

The state-sponsored single-buyer insurance regime has been Beijing’s most ambitious health reform by far. Aged care and medical financing were envisaged standing on three-pillars: medical assistance (a safety net for low income patients with major illnesses), the BMI and commercial insurance. Medical bills can be paid by BMI, employer-sponsored supplementary medical insurance schemes or commercial medical insurance.

A ‘welfare state’, is not the aim, rather a dynamic market in which the state only covers essentials. Safety nets and core functions are provided; supplements are left to individuals and the market. Medical insurance is to provide a strong third pillar backed by the private sector, including international insurers.

centralised procurement to build a pharma powerhouse

The NHSA holds decisive power in cost cutting and protecting local players. Centralising procurement under the agency’s remit addresses long standing issues with medical supplies. From the 1980s until 2006, each hospital bought drugs independently, affording pharma companies lucrative arbitrage opportunities. Safety and quality issues were rife among the many small-scale manufacturers, compounded by inefficient distribution with intermediaries inflating costs. In 2008 provinces started piloting provincial-level collective procurement. National level centralised procurement was launched in 2018.

The new procurement regime for drugs and consumables is reorganising the pharma market. Nationally at least 300 medicines will be centrally procured by end 2022; 500 by 2025. A nationwide system is set to monitor drug prices, and supply all public and private hospitals as well as pharmacies. It includes the pharma credit evaluation system, which has already rated five firms as ‘seriously dishonest’ for cutting supply or offering kickbacks.

Domestic firms are gaining a greater market share for centrally procured generics. Low returns are forcing them to move into more profitable products and innovate more. A smaller number of leading firms will have better R&D. This will then set the PRC on its path, ordained in the 14th 5-year plan, to becoming a pharma powerhouse by 2035—globally as well as domestically. Streamlining approval and evaluation will continue; developing a protocol suitable for TCM (traditional Chinese medicine), currently excluded, is a priority. Five rounds of central procurement completed as of end 2021 have seen the rules settled down. More drugs are to be included; biosimilars, (drugs that are similar but not identical as with generics) like TCM, remain excluded.

tech self-reliance

cultivating indigenous R&D

Beijing frets that much frontier R&D remains in the hands of global players outside the PRC. Strengthening basic research to support frontier work and break innovation ‘strangleholds’ is paramount in Beijing’s current thinking to build competence across scientific disciplines and, not least, to safeguard national healthcare security.

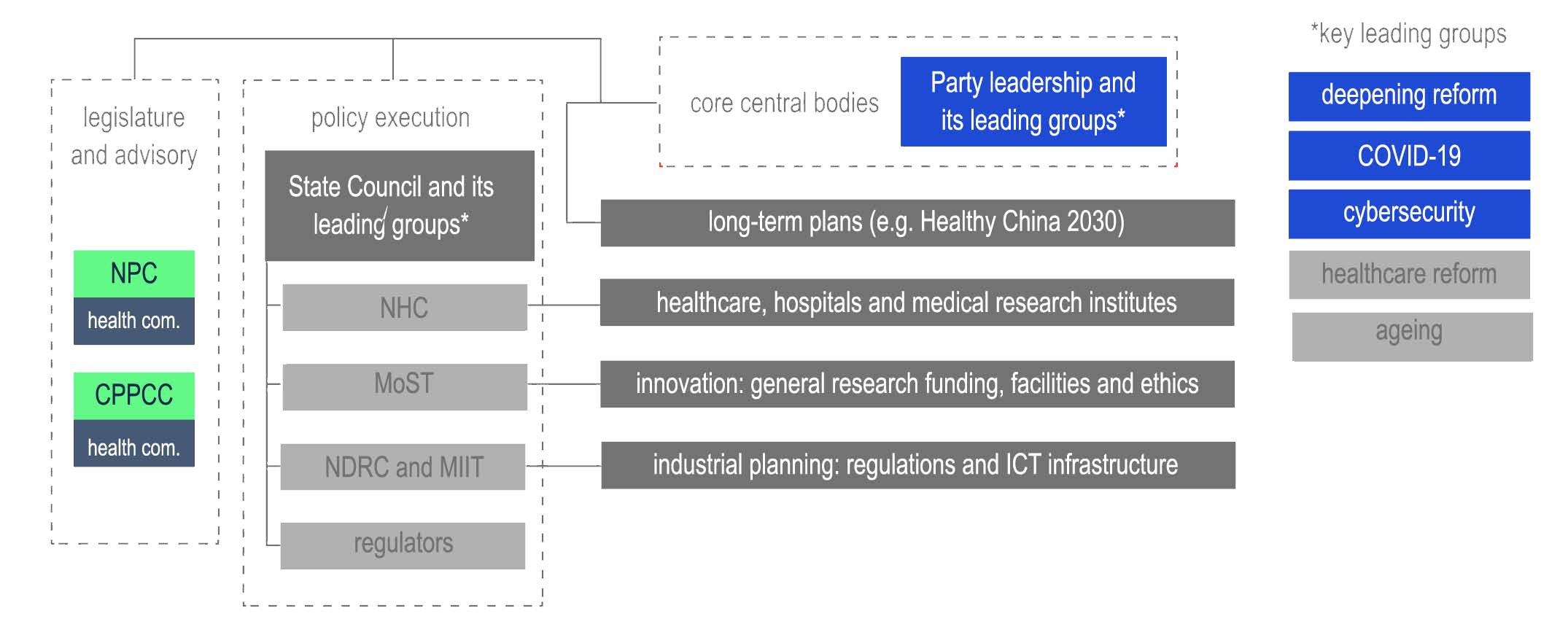

Despite momentum in the wake of COVID-19, effective rollout entails re-engineering governance of health technology. Reorganisation and reform in recent years has provided an institutional framework. Chart 3 outlines the overall agency remits and the ministries responsible for health tech.

But at the frontier, erosion of academic norms under the Xi Jinping administration threatens the very scientific breakthroughs the Party demands, as evidenced by recent disciplinary actions.

chart 2: policy making structure for health tech

source: State Council; NHC; MoST; MIIT; NDRC

Streamlining approvals for imported drugs was proclaimed in June 2017, when Beijing joined the ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use). Shrinking backlogs in medicine registration, the change benefits global pharma firms, with fast approvals for medical data access, clinical trials and marketing. Fast-tracking registration complements Beijing’s tactics for tech transfer in pharma R&D for

- patent application

- pre-clinical development, including acute toxicity, and pharmacology

- chronic toxicity

- clinical trials in each of the three phases

- registration and market authorisation

- pricing and insurance reimbursement

advancing biopharma research

To fix quality, bioequivalence testing (to certify that a generic version has comparable bioavailability to the original brand) was launched; to cut prices, centralised volume-based procurement followed. Serious price drops resulted.

The industry has seen rapid consolidation: domestic pharma is approaching critical mass in the market. Similar tactics for medical devices are in train.

Biosecurity regulation keeps tightening. Control over human genetic and biological (including animal and plant genetic) resources gained teeth from the Biosecurity Law. Fast-tracked by Xi for passage in October 2020, the law speaks to a range of security measures, including a ban on collection or storing of human genetic resources by international entities operating in the PRC. Global actors may trial drugs only in collaboration with domestic partners. Received for the most part positively by domestic pharma, the law, in their view, supports their bids to be global players.

Amendments on how pathogens are managed in microbiology labs are awaited.

‘Active health and ageing tech-nology solutions’ NKP

(national key R&D program)

This NKP program funded 22 3-year projects, with a C¥580 million budget in 2020; another eight 2-year projects with a C¥55 million budget in 2021. Preferred R&D areas include

- an old-age health and nutrition monitoring database

- prevention, treatment and care

- technologies for common geriatric diseases

- smart care algorithms, solutions and equipment

- solutions for enhancing quality of life in old age

- elderly and integrated care units

The program is open to public and private research, medical institutions and private enterprises. Local governments will fund half; Beijing will provide one third.

fostering international ties

managing healthcare FDI

The PRC regularly renews efforts to attract FDI (foreign direct investment) across a range of sectors lacking the skillsets found in advanced economies; Beijing must however always be firmly in control. Hence medical and aged care markets have been, and will remain, friendly to FDI. As the PRC opens its service industries, overseas investors will move into care provision and insurance. But constraints on bio-sensitive research will tighten.

WFOEs (wholly foreign-owned enterprises) in medical services are not yet approved to operate in pilot free trade zones or elsewhere. According to the FDI negative list (detailing investment rules for international capital last updated in 2020), PRC investors must hold at least a 30 percent share; the minimum investment should be C¥20 million with a maximum operating period of 20 years.

The industry park model, in place for more than two decades, is likely to continue for foreign pharma and equipment firms, with preferential conditions for WFOEs. In the service sector, foreign investors may hold a maximum of 51 percent in PRC-based insurance firms; lifting this bar, to give WFOEs more autonomy, is currently on the table.

Technically, international life and pension insurers have had access to the PRC market since its 2001 accession to the WTO, but have been limited to the premium end, struggling to make a profit in the closely protected market. A round of ‘opening up’, targeting the service industry, was called for in 2018, improving the operating conditions for international insurers like Heng An, BOB Cardif Life. COVID precluded entry of other international players into the market in 2020–22, but expect to see it back on the agenda soon.

table 1: key FDI regulations

Heng An Standard Life 恒安标准人寿

The PRC’s first pension insurance joint venture, Heng An will be its ninth commercial provider. With C¥200 million in registered capital, its parent companies (Standard Life Aberdeen, UK and Teda Holdings, Tianjin) each hold 50 percent of its shares. Regulators expect more international insurers to enter the PRC market.

BOB-Cardif Life 中荷人寿

Funded by the Bank of Beijing and France’s BNB Paripas Cardif, since 2002, the Dalian-based company controls C¥50 million and has seven branches in eastern China. Despite several board reshuffles, its performance has been stable over the last decade. It was rated an A-class insurer in 2019.

cross-border care provision and clinical trials

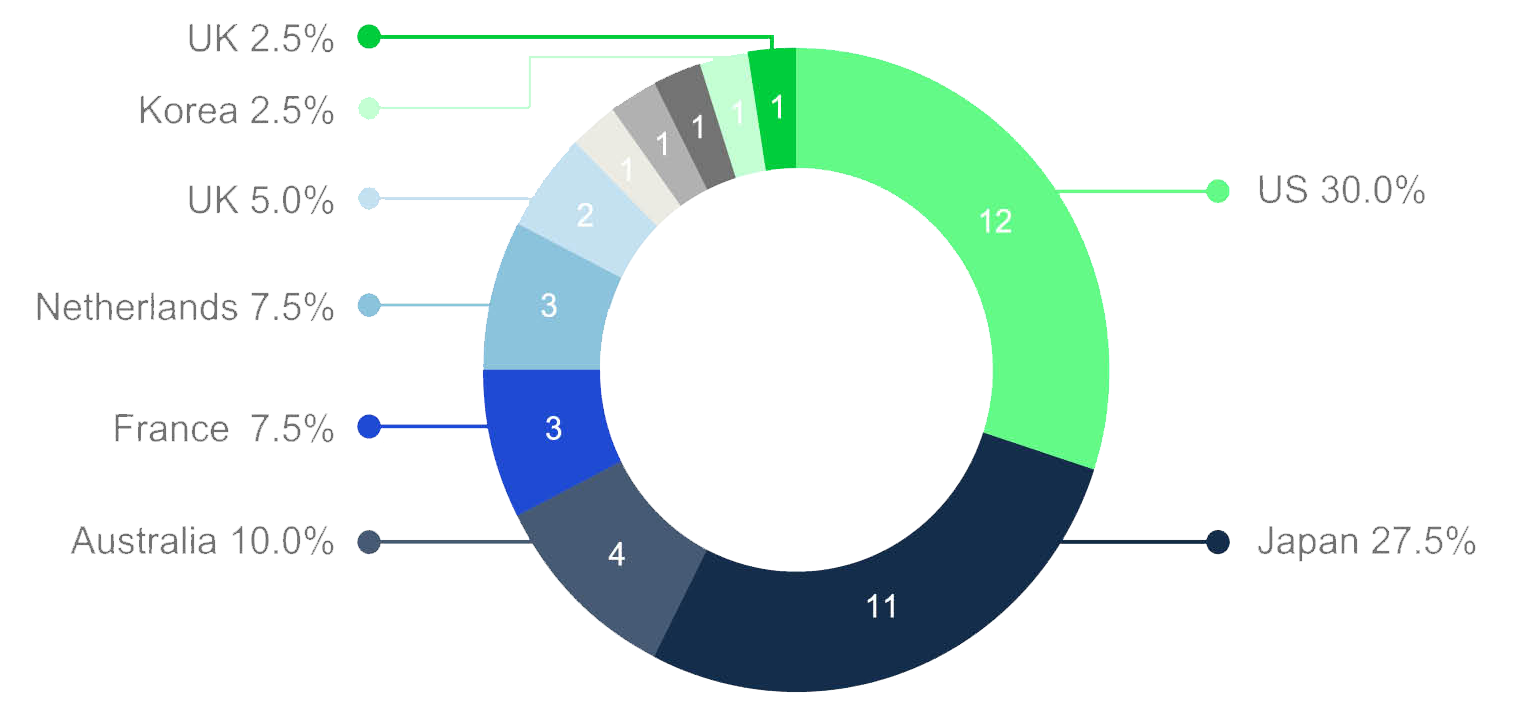

International actors are welcome to engage in cross-border care provision and clinical trials. US and Japanese firms are the most prominent global players in the PRC market, setting up branches in tier 1 cities, then expanding into the lower tiers (see chart 3).

chart 3 : international collaboration in cross-border aged care provision in China

source: Age Club

Since COVID-19, emphasis on innovation and streamlined import procedures have made it easier to bring in new drugs. Apart from the changes to administrative processes discussed earlier, authorities are positioning Boao in Hainan as an international medical tourism zone. Global pharma are allowed to use new drugs and medical devices there and collect data to prepare for entry into China.

The National Medical Product Administration has, indeed, allowed RWE (real world evidence) to be used in gaining approvals. RWE for instance was the basis of the approval granted in March 2020, within six months and the first of its kind, for Allergan’s glaucoma treatment. The Patent Law, currently under revision, will protect innovative drugs for up to 14 years after market launch.

In online healthcare and biotech, foreign firms may not collect or store genetic data. Given volatile global tensions and their expression in Beijing’s dual circulation strategy (see CEB 3 ‘macro economy and dual circulation‘) that calls for strengthening the domestic economy, the general outlook is not overly optimistic.

Despite tougher data and privacy protection, space remains for global firms to operate. Hints have been given of greater tolerance of cross-border data flows. ‘Grading classification + negative list’, (Beijing’s supervisory scheme that assesses a firm’s access to data based on their operation, country of origin, size, etc) will be upgraded—provided firms are not banned by the foreign investment negative list.

Massive state-led promotion of health ‘big data’ began in 2017. A raft of social issues were targeted: high-quality grassroots healthcare, support for multilevel and online care, and rollout of new digital healthcare tech and products.

Four major SOEs are involved

- National Healthcare Big Data Industrial Development Group

- National Healthcare Big Data Tech Development Group

- National Healthcare Big Data Holding Inc

- National Healthcare Big Data App Development Group

They are to collect and process complete suites of patient data for input into research algorithms. They will help build infrastructure in healthcare clusters, and incubate market-ready innovative firms. Led by NHC and supervised by a National Healthcare Big Data Security Management Committee, progress has been poor.

four national health big data groups (central SOEs)

digitalisation

state-led health data management

Building and professionalising multilevel healthcare cannot get far without ICT. It can streamline procurement and service provision by sharing patient records, facilitating remote healthcare services, tracking drug production and integrating payment and reimbursement.

Partnership with PRC firms helps global firms make competitive bids, leveraging their data management tech. Expertise is welcomed in

- medical insurance systems integrating administration, intra-province profile sharing, service pricing, credit evaluation, payment, big data application and auditing systems

- medical facility ICT, including hospital and clinical information systems in tandem with sub systems and platforms, especially clinical records databases

- cross-region platforms for sharing data nationally and between agencies and institutions

- data protection via blockchain

- integration of advanced medical equipment data (generally imported) into patient records

Citing national security, Beijing and local agencies pressure overseas firms to transfer tech and/or IP to PRC partners, regardless of home-country corporate practice. There is similar pressure to comply with rules on where medical data processing can be located, and on ownership of results.

Electronic medical records, decision support, data capture, diagnostic-related groups and smart service classification in hospitals are promising fields for applications of medical data.

market-driven AI diagnostic industries

Backing 21st century frontier medical tech via major investment and reconfiguring the sector, Beijing is confident that it will lead in key sectors like medical AI and medical data, without relying on overseas collaborators.

The 2020–30 AI development plan sets out goals for five major areas of health AI: medical imaging, assisted diagnostics, pharmaceutical R&D, health management and disease forecasting. The private sector is on notice to work with educators in incubating talent, helping develop hard and software infrastructure for AI diagnosis in hospitals, and commercialising the tech.

AI diagnosis would ideally make up for the shortage of PRC pathologists, whose number per capita is a mere tenth of the 2015 EU average. Given the need for it, feasible reform pathways include

- improving sample quality control; staff training is needed

- training for health institute staff (both medical and administrative) on AI applications, including for specific illnesses and treatments

- developing AI diagnosis as part of genetic sequencing

- better diagnostic systems with greater algorithmic and analytical precision

- transparency allowing comprehensive ethical review and avoiding ‘data black boxes’ in clinical trials

- integrating pharmaceuticals into AI diagnosis; using AI as part of R&D and analysis of virtual clinical trials

- preventative monitoring with AI and disease forecasting

- exploring the ethics of AI health applications

WeDoctor Group: forerunner in AI diagnostics 微医集团

Poor grassroots care drives patients to overcrowd central hospitals. Sensing opportunity, remote care service provider the WeDoctor Group emerged in 2010. First an online hospital queuing platform, it now embraces big data and AI. A mobile AI diagnosis unit it developed brings services to the patient.

This mode of care makes physical and follow-up checks available for chronic conditions, patients signing on with family doctors, keeping personal health files and receiving health education.

Cooperation with Pingdingshan, a prefecture in Henan, began in 2017. WeDoctor supplied a county with 12 mobile units able to identify thousands of diseases. Hearing about the pilot at a 2019 Beijing Forum on Healthcare Big Data, NHC officials drew lessons from its success. As of end 2020, WeDoctor had opened 27 online hospitals, servicing over 18 million remote care visits. WeDoctor applied to list on the Shenzhen stock exchange in July 2021.

looking forward

Beijing safeguards its domestic health and aged care industry via a mix of measures, balancing centralised procurement, digitalisation, cross-border medical research collaboration and universal healthcare insurance. Provided they comply with red lines on domestic politics and national security, international providers may find opportunities: Beijing’s commitment to a society that despite ageing is well-provided for, is unlikely to diminish.

However, for the moment, the industry’s prospects remain hostage to Beijing’s commitment to zero-COVID. Highly politicised, COVID has escalated beyond a public health issue. Despite penalties currently levelled at overzealous official prevention and control, not least in blocking logistics, relaxation of lockdowns in favour of economic imperatives is off the table—at least publicly—for the rest of 2022.

Opportunities are still in store for Australian partners in such areas as commercial insurance, specialised medical care provision, long-term care, health tech and biopharma research. But cooperation will remain difficult until the current COVID-19 chaos is under control and Beijing’s healthcare reform agenda is back on track.